Read What You Wish

I have a few writer friends, but one of them stands out from the rest. Possibly because he is more familiar with my work than any of the others, possibly because we were roommates for years, and possibly because I trust him to give good, thoughtful feedback and to read with care. Our writing styles and respective genres are quite different, but it is his opinion I trust above the others. Experience, loyalty, and honesty go a long way. As such when he points me to an article, I read it because, chances are, it will make me think. This week, he posted an article from the web magazine Slate in which the writer claims that adults who read young adult literature (YA) should be ashamed of themselves. It was originally posted this summer, so it’s been circulating for some months. Just from the sheer number of comments on the article, it has done quite the job of getting folks talking. I spent only a little time perusing the comments as there were some 3.1K at last check, but as expected, many disagreed and a fair number agreed. Some were out right offended and angry. So for what it’s worth, having written two novels that are shelved in the YA category, here are my thoughts on the matter.

To begin, I did read the article in its entirety and believe the title to be quite unfair – both to its audience and its author. The title simply stirs up contention and, of course, gets stupid web traffic (which is probably what all of this was about in the first place rather than actually prompting meaningful thought and self-reflection). The title is sensationalized and makes older readers of YA feel attacked, not fair. It’s unfair to the author’s point as well and not a good representation of it. A sizeable portion of her argument focused on maturity, ie. mature readers should read quality literature that makes them think. Well ho hum, I actually agree with that, and the title does not reflect this stance in the slightest.

At the crux of this topic lies a problem that is often overlooked by readers and glossed over by publishers and academics – how we classify books. Really, what is a YA book? Is it a book about young adult struggles? A book that features a young adult as the protagonist? A book written on a specific reading level? A book written for a teenager audience? The delineations aren’t as clear-cut as we would like them to be. Often, a book will be thrown into the YA category simply because it meets one of these criteria. Personally, I feel that a YA book should be written for an audience of teenagers and possible early twenty-somethings, but that’s not necessarily how books and stories are viewed within the academic community and by publishers. I was told during my graduate studies that main characters should roughly match the age of the intended audience, and that causes all kinds of problems. Not all stories with youthful characters should be read by a young audience, and not all young audiences are going to be attracted to books about young people. Are we saying that books featuring aged protagonists should only be read by the elderly? Stories are just more complicated than that. For example, consider Irish author John Connolly’s The Book of Lost Things. While featuring a young protagonist, its content was not written for the average twelve year old, and average twelve year olds (even many in their late teens) wouldn’t find it appealing. Of course, there will always be some readers who are advanced for their age brackets and could digest the book just fine. Without a better way to categorize, it’s very hard to determine which books fall into the “No, no! Bad Adults! You shouldn’t be reading that!” category. I think we would all agree there is an enormous difference between Catcher in the Rye, The Chocolate War, The Giver, and Twilight, yet you will find them shelved in the same section.

So what do we do with these awkward books that may have adult appeal but feature younger protagonists? As a writer, it is a question with which I struggle. Who really is the audience for The Kyla: Call and The Kyla: Return? Why is it that I thought one group would devour it, but turns out, it’s more appealing to another? Probably because stories have the ability to transcend silly, human-conceived boundaries. They make someone else’s world accessible to readers, and that ability is what makes these stories effective. There are many connections and identifications readers can make when reading a story, and they aren’t all about age, race, or gender.

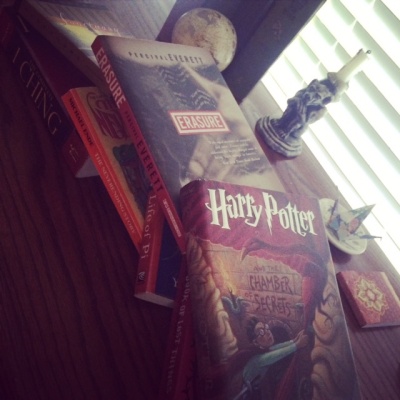

When I was twelve years old, I read Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage. It wasn’t an easy read for me, but it still engaged me. I was not its intended audience. As a graduate student, I revisited Where the Wild Things Are. It still engaged me, and as an adult reader, I could appreciate the work in a much greater way. I was not its intended audience. Also as a graduate student, I read Percival Everrette’s Erasure. It was one of my favorite reads from grad school. I found it brilliant and may have been part of the intended audience, but I’m not really sure.

I don’t believe that just because a book is written for teenagers or a child it has no application to adult life. Even if an adult, like myself, does not have children, it is important to remain in contact with the world of children. It is also important to remain in contact with the world of the aged. Being ashamed to read a book because it is not written for your age bracket is ludicrous, but being stuck in one genre… Well…

I don’t believe that just because a book is written for teenagers or a child it has no application to adult life. Even if an adult, like myself, does not have children, it is important to remain in contact with the world of children. It is also important to remain in contact with the world of the aged. Being ashamed to read a book because it is not written for your age bracket is ludicrous, but being stuck in one genre… Well…

I return to the article author’s point about maturity. An immature person is one who is lacking development. Now, this could simply be a child or an adult who is stuck in a developmental stage. But let’s just replace “stage” with “genre” for the sake of my point. People can get stuck in a lot of places, and I don’t feel it’s any worse for an adult reader to be hung up on YA literature anymore than it is for an adult to be hung up on Romance, Science Fiction, Western, Southern Lit, General Lit…. The list goes on. If like the article author states, this really is about reading development and challenging ourselves, then we shouldn’t be stuck in any genre.

And that is how I approach reading. I just finished James Maxwell’s Enchantress. I’m currently reading the Huang translation of the I Ching, and I am picking up James Joyce’s Ulysses next. I enjoyed and admire Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian (though The Road is my McCarthy favorite) while I also enjoyed and admire Ender’s Game and The Wizard of Earthsea. Reading allows us to experience what is otherwise inaccessible to us. We can and should experience diversity.

Sometimes that’s a twelve-year-old girl reading Moby Dick (yeah, I chomped on that one too). Sometimes, it’s a fifty-year-old reading Harry Potter.

While most of you know it as an 80’s movie, The Neverending Story is a fantasy novel for young readers penned by German author Michael Ende. In the book, before protagonist Bastian saves Fantastica from The Nothing, the Childlike Empress forces the story into a cycle – the last event spawning the first event of the story. It creates a terrible succession (thus the title) that drives Bastian to the point of overcoming his fear and taking new action to break the cycle and save his sanity. Perhaps we should take notes for our own reading lists, and for those of you who are worried about your fellow readers, don’t be. Your responsibility has always been for your own development – not your peers’. And perhaps if you suggested that adult novel you read and maybe added why you liked it, their attention just might be piqued, and you just might have the privilege of introducing them something new that will challenge them. You might just be the Childlike Empress handing the Auryn to Bastian, and then your peers might just turn it over and find “Do what you wish” inscribed on the back.

Leave a Reply