Why You Should Read The Giver…Even If You’ve Seen the Movie

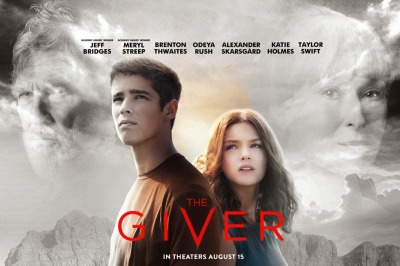

A couple months ago, I squealed a little in the movie theater as I watched the trailer for The Giver the first time. This is not an abnormal reaction for me when I realize I’m going to get to see a beloved book come to life. A few weeks ago, the film was released, and this past week, Mike and I finally got around to seeing it. I’m glad we saw it. That said, I’m not going to talk a whole lot about the movie. Why? Like my experience of the Cloud Atlas film, I feel the screen version lost some truly defining characteristics in the translation of mediums, and I prefer to talk about the stuff I like. That aside, it presents me with an excellent opportunity for talking about the book because people are thinking about it. For a thorough film review, cruise over to the Queen’s Logic blog. While the film retained more of the plot than I expected and many of the underlying themes, the novel’s narrative unfolds with a subtlety that complements its setting and themes, but this subtlety is completely lost on the film. With a deft hand, author Louis Lowery weaves a story that horrifies and inspires, one that conveys important truths but does not smack the reader upside the head with them. The way in which the story is told plays a significant role in why it is so special. If you aren’t going to read the book, definitely see the movie, but even if you have seen the movie, please read the book.

A couple months ago, I squealed a little in the movie theater as I watched the trailer for The Giver the first time. This is not an abnormal reaction for me when I realize I’m going to get to see a beloved book come to life. A few weeks ago, the film was released, and this past week, Mike and I finally got around to seeing it. I’m glad we saw it. That said, I’m not going to talk a whole lot about the movie. Why? Like my experience of the Cloud Atlas film, I feel the screen version lost some truly defining characteristics in the translation of mediums, and I prefer to talk about the stuff I like. That aside, it presents me with an excellent opportunity for talking about the book because people are thinking about it. For a thorough film review, cruise over to the Queen’s Logic blog. While the film retained more of the plot than I expected and many of the underlying themes, the novel’s narrative unfolds with a subtlety that complements its setting and themes, but this subtlety is completely lost on the film. With a deft hand, author Louis Lowery weaves a story that horrifies and inspires, one that conveys important truths but does not smack the reader upside the head with them. The way in which the story is told plays a significant role in why it is so special. If you aren’t going to read the book, definitely see the movie, but even if you have seen the movie, please read the book.

*Potential Spoilers Below*

In the novel, the main character Jonas is considerably younger than in the film. He’s actually eleven for much of the book. Lowery spends considerable time immersing the reader into Jonas’ world (a.k.a. The Community) before Jonas is assigned his role. At the very beginning of the novel, everything feels futuristic but still fairly normal. It’s just a community of people living out their lives, but as the story progresses events, dialogue, and descriptions of the environment are peppered with elements and occurrences that seem off kilter to the reader. Because of this, the reader beings to understand that something isn’t just wrong. It’s very wrong. The order in which these occurrences are presented causes the reader’s apprehension to grow. This tactic is a set up and a brilliant one at that. It makes us more receptive to the truth when we finally realize that people not only no longer remember history but they have also lost their ability to experience emotions and a full life.

Subtlety also makes the reader’s realization that there is no color in The Community more poignant. The novel takes a third-person closed perspective. So though “I” isn’t used, even when we are basically hearing Jonas’ thoughts, the reality we are presented with is his reality and no one else’s. Jonas doesn’t realize this world is all shades of gray until about half way through the book. He does see flashes of color, but he can only think that objects change for just a moment. He doesn’t know what he’s seeing, so he can’t accurately describe it. Quite the paradox considering his drive to be precise in language and The Community’s emphasis on it. The film begins in black and white with splashes of color appearing occasionally. Yes, that is a literal translation of the story’s reality, but part of the beauty of The Giver is the reader’s quest to discover what is missing and what is wrong. The black-and-white is a dead give-away. Was there a better way to convey it? I can’t think of any at the moment given the visual medium, but this tactic didn’t produce the same affect as the slowly revealing prose.

In the novel, Fiona and Asher cease to be important characters once Jonas begins his training with the Giver. They don’t help him. This is actually very important to the overall effect of the story. The Community has denied its citizens’ the ability to be true individuals. Yes, they match each person with a career that fits his/her personality. However, being an individual implies a degree of separateness and the ability to make choices and effect changes on the world. Once Jonas becomes the Receiver, he begins his journey toward becoming an individual, and that, by definition, must occur in isolation. This fact, also gives more weight to the end of story where Jonas truly becomes an individual by taking responsibility for Gabe and fleeing. Yes, he has baby Gabe with him, but Gabe cannot give Jonas guidance or help him make decisions. Gabe’s dependence on Jonas and Jonas’ sense of responsibility for the infant can only fortify Jonas emotionally. The child can’t tell Jonas what to do.

Finally, within the pages of the novel, the reader becomes acutely aware of the weightiness of Jonas’ and the Giver’s decision to release the memories back into The Community. In the film, this was glossed over. Descriptive passages of the painful memories and what goes through Jonas’ head and body during these experiences brings both the contrast and relationship of rapture and agony that much closer to the reader. One is required to ask, “Is all the joy and beauty worth the pain and ugliness?” The decision at which Jonas arrives is not an easy one, and he makes it while truly understanding what was gained and lost when the memories were banished. Unfortunately, he and the Giver alone can truly appreciate the elimination of suffering caused by differences and negative emotions. Conversely, only they can see how monstrous their community has become because there are no feelings or sense of empathy. As a result, they are the only ones equipped to make decisions, and they aren’t truly allowed to make them. Will the reader arrive at the same conclusion as Jonas? I can’t imagine why one wouldn’t, though I rarely embrace absolutes, especially when it comes to people.

Do yourself a favor and read The Giver. It’s easy, relatively short, and more captivating than the film. Not only will you be entertained, but you will have thought about some very important life questions. And that is the mark of a truly great story.

Leave a Reply